Arrow Tuning For Beginners

What does one do after purchasing a brand new bow? Buy some arrows of course! But which arrows do you buy? If you’ve gone to a proper archery shop to get set up, you would do well to listen to what they say in terms of arrow selection.

Hunting and target archery generally require different arrow attributes, so it is good to have an idea of what you will be using your new bow for. But what if you’d like to try some different arrows? Or raise the poundage of your bow? What about a trying a different point weight? All of these factors can really affect the tune of your arrow to your bow.

It is especially good to check your arrow flight before you start screwing flight-altering broadheads to the front of your arrow.

Without getting too technical with arrow and bow tuning, hopefully you can get an idea of some of the forces at play, how to check your arrow tune and how to tune your arrows for great arrow flight.

Archer’s Paradox, Spine, and Dynamic Spine

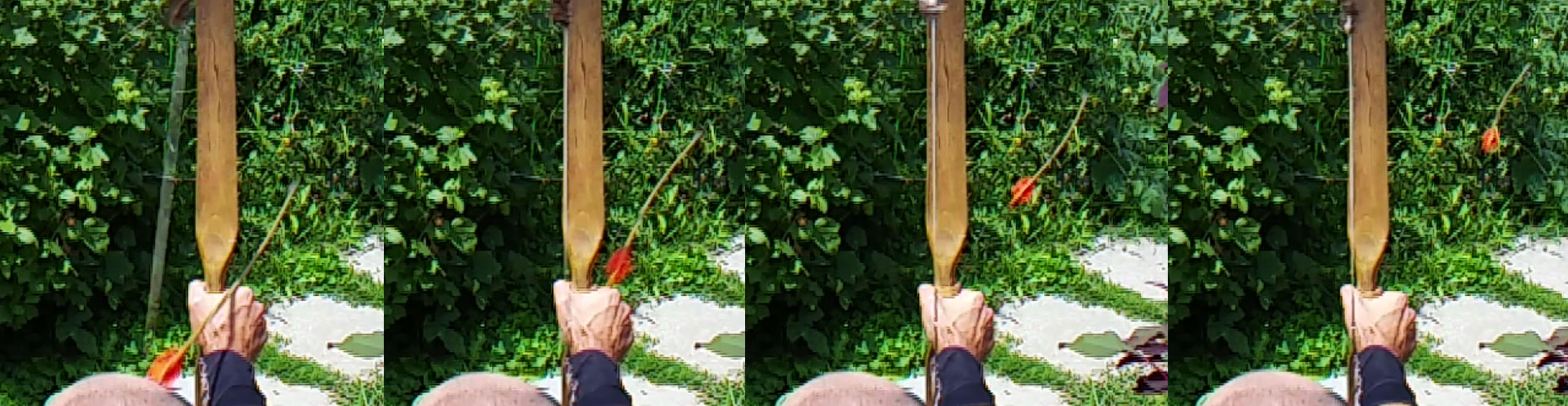

When an arrow is shot out of a bow, compound or traditional, it undergoes what is called archer’s paradox (see the picture below). There are various definitions for it, but it describes the effect of an arrow bending upon being shot. The arrow bends around the riser, and continues to flex back and forth on its way to the target. There are some great slow motion videos on the internet that catch the paradox of the arrow in flight. What seems fairly inflexible in the hand becomes a piece of wet spaghetti when shot out of a bow. Because the arrow is being pushed from behind, it bends as the nock end of the arrow accelerates faster than the point end of the arrow. How much the shaft bends affects the impact point of the arrow left and right. This is where the spine of the arrow comes in.

Archer’s paradox

The spine of an arrow (not ‘spline’) is a measurement of it’s stiffness. For some carbon arrows (I say ‘some‘ because companies like to come up with their own stiffness codes) spine is expressed in the amount of deflection in thousands of an inch. For an Easton 500 carbon shaft, a 1.94lb weight suspended in the middle of a 28” section of shaft would cause a deflection of .500” or a half inch. So, an Easton 600 is a weaker shaft, because the deflection is .600” for that same weight.

For wood arrows, spine is measured in pounds. The shaft is initially measured in a similar way, a particular weight suspended on a particular length of shaft. Those deflections are then associated with a poundage, which serves as somewhat of a shortcut when matching arrows to your bow. But that only really serves as a starting point. An arrow, in order to shoot accurately, must flex just the right amount when shot.

For a right handed archer, an arrow that is too weak in spine will shoot to the right (bending too much) and an arrow that is too stiff will hit left (not bending enough). In order to make an educated guess on which arrows you should buy for your bow, you should consult a spine chart. There are dozens of these charts floating around the internet and they will take into account your bow poundage, draw length and point weight and put you in the right ballpark in terms of arrow spine. Consult these before buying shafts. Once you’re in the ballpark, the fine tuning comes in. To understand the variables that go into tuning arrows, there must be an understanding of dynamic spine.

Remember the fact that every characteristic of the arrow affects how well it shoots? Spine, (sometimes called ‘static spine’) is only a very general way to group shafting. Dynamic spine is what really affects how an arrows tunes to your bow. This is the complex interaction between shaft length, point weight, static spine, center-cut of your bow, draw length, bow poundage and brace height.

To a lesser extent shaft diameter, shaft weight, shaft taper, string material and your own personal form comes in to play. The largest factors affecting the dynamic spine of your arrow are static spine, which we already understand. Shaft length, point weight and center-shot of your bow riser are other big factors in dynamic spine. Here is a quick guide to how these large factors affect the dynamic spine.

Arrow Length: Cutting an arrow shorter will make the shaft dynamically stiffer. Long arrows, weaker dynamic spine. This is because it takes less force to flex a long piece of material than a very short piece.

Point Weight: A lighter point weight will stiffen the dynamic spine, a heavier point will weaken it. This is because a heavier point has more inertia, and will therefore resist acceleration more than a light point, this causes the arrow to flex more upon the shot.

Center-Shot: The further from center-shot your bow is, the stiffer arrows will behave. In other words, the more center-cut your riser is, the stiffer the spine you require. Self-bows with no cut-out shooting window require much weaker spines because the arrow must flex around the entire handle

Draw length, bow poundage and brace height come into play with tuning. You can’t crank your bow up by 10 pounds and expect your arrows to still be tuned like they were when you were shooting before (unless you were already shooting arrows that were too stiff) Changes in bow poundage, draw length and brace height all affect the tune of your arrow, and although your arrow flight may seem good, it may be very different once you screw in a broadhead to the front of your arrow. Broadheads amplify tuning issues that field points do not. With today’s fast arrow speeds, every difference in the aerodynamics of your point or broadhead changes things. Air resistance is proportional to velocity squared at high speeds. That mean the faster your bow, the more important tuning is.

Checking your arrow tune: Bareshaft and Paper Tuning

So, how does one check their arrow tuning? Generally, there are two ways, and lots of conjecture as to which one is superior. Bareshaft tuning, is generally more suited to those of us who buy raw shafts, have access to arrow saws, and assemble arrows ourselves. Paper tuning would be best for someone who buys pre-fletched shafting. Some find a mix of both works well.

Barshaft shooting involves unfletched shaft from your bow. By subtracting any steerage offered by the fletching, you are really seeing what the arrow wants to do when it is shot from your bow. It is good to start out at shorter distances (5 to 10 yards) and see what happens. As you dial your arrow in, the distance can be increased to fine tune the flight.

For bareshaft tuning, some use how the shaft lays in the target as an indicator (this works best with horizontally layered targets, where the arrow can enter on a slight angle).

For a right handed archer, a weak shaft will lay in the target with it’s nock the the left of the point. Stiff shafts will show the nock to the right. If your arrow has entered perfectly straight, take a few steps back and see what happens from there. When your shaft enters the target perfectly straight from 20 yards, you can be reasonably assured your arrows are tuned to your bow.

Results of bareshaft tuning

Another way to bareshaft tune is to take 2 bareshafts and 4 fletched shafts and shoot a group. If your shafts are weak, your bareshafts will hit to the right of the fletched group. If they are stiff, they will hit to the left. Reverse that for a left-handed archer. Well tuned arrows will hit within your fletched groups.

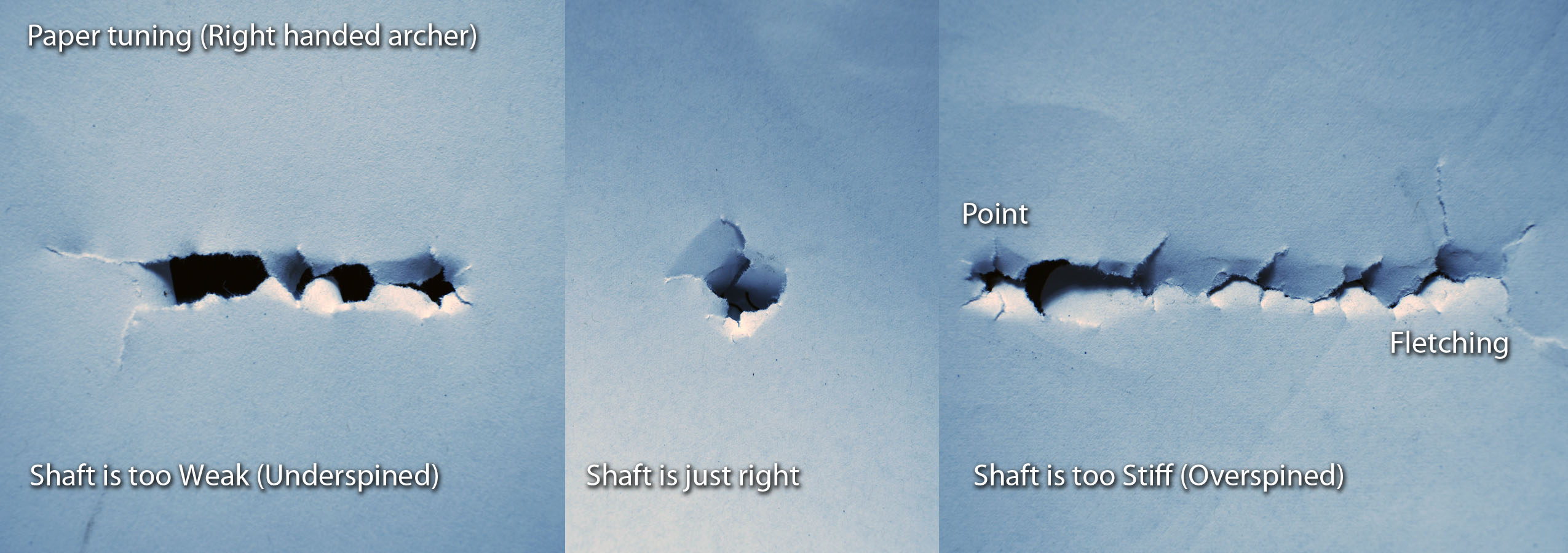

Paper tuning is the practice of shooting fletched shafts through a sheet of paper at close distances (3 to 5 yards). The resulting tear in the paper will give you a snapshot of how your arrows are leaving your bow. A perfect tear is often referred to as a ‘bullet hole’. This will take a bit of set-up as you need to suspend a sheet of paper in front of your target. It should be infront by at least a full shaft length to avoid interference as the arrow enters the target. A tear to the left of where the point enters the paper means your shaft is weak.

If you can picture it, the arrow flew through the paper on an angle, with the point to the right and the nock to the left. This means your shaft is bending too much when shot. The opposite, a right tear, indicated a stiff shaft. The arrow is coming out of your bow with the point to the left and the nock to the right, meaning your shaft is not bending enough.

A perfect ‘bullet hole’ with three tiny fletching tears is what we’re trying to achieve. Tears high and low, indicate nocking point problems and can be fixed by moving the arrow up and down the string. Paper tuning out to longer distances is not as necessary because the fletchings will have corrected any problems with arrow flight by then.

Results of Paper Tuning

Fixing your Arrow tune: Tune your bow to your arrow or your arrow to your bow?

Tuning your arrow to your bow is a practice that most traditional archers are familiar with. There is not much in terms of tuning that can be done with a traditional bow, so it is most logical to tune your arrows to you bow. To correct a weak shaft, you can:

- Decrease point weight

- Build out your strike plate, with leather etc (making your bow less center-cut)

- Cut your arrows shorter (1/4” or 1/2” increments)

- Reduce brace height (less desirable)

- Switch to the next spine grouping stiffer (requires buying new arrows)

To correct a stiff shaft:

- Increase point weight

- Switch to a thinner strike plate material (making your bow closer to center-cut)

- Increase brace height

- Switch to the next spine grouping weaker (requires buying new arrows)

There is generally more and easier options when you have a weaker shaft than a stiffer one, which is why many people start out slightly weak and cut down their arrows until the shaft hits perfectly.

Tuning your bow to your arrow is easier to do with modern compounds with adjustable poundage and some modern ILF recurves with plungers and movable arrow rests. That being said, you need to be in ballpark already, and most folks will still make alterations on the arrow before messing around with their bows. Some of these would also result in small reductions in speed. Remember, speed isn’t everything, and a well tuned arrow will penetrate better than a fast, out of tune arrow. So, To correct a weak shaft:

- Move the arrow rest further out from center-cut

- Reduce poundage in small increments

To correct a stiff shaft:

- Move the arrow rest to closer to center (if not already)

- Increase poundage in small increments

Bringing it all together

It is up to you to decide what method will work best for you and how to get there. Generally, any large changes that need to be made should be done to the arrows and not your bow. The bow can be used for some very fine tuning. Consult an online spine chart to get in the right ballpark.

Many people purchase full length shafts that they know will be weak and cut them down in increments as they approach their perfect arrow length. You can also purchase test kits for carbon shafts and point weight test kits. There is not a better way to understand tuning than playing around with different spine shafts and different point weights. Try not to get bogged down in seeking exact numbers, be it poundage, total arrow weight, or arrow speed. “I need to shoot 60lbs”, “I need to shoot 300fps” etc. A well flying arrow from a lighter bow will be more accurate than a poorly tuned arrow from a heavier bow, and shot placement and arrow flight count for more than raw poundage and speed.